MODERN HISTORY OF AMERICAN COLONIES

LECTURE 2

MODERN HISTORY OF AMERICAN COLONIES.

Colonization and Settlement. Dutch in America: 1624-1664. Original Thirteen Colonies. The war for independence of the British colonies in North America. Other British colonies: Newfoundland, Rupert's Land (the area around the Hudson Bay), Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, East Florida, West Florida, and the Province of Quebec.

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT. American colonial history belongs to what scholars call the early modern period. As such, it is part of a bridge between markedly different eras in the history of the western world. On its far side lies the long stretch we call the Middle Ages (or the “medieval period”), on its near one the rise of much we connect with modernity. Portugal and Spain, having launched the so-called Age of Discovery at the end of the fifteenth century, laid claim to most of what is today Central and South America. The British, and others from northern Europe, were latecomers to the imperial contest. As a result, their entry, beginning around 1600, was channeled toward what was left—chiefly, the Caribbean islands and the cold, apparently hostile and frightening, coastline of North America.

European nations came to the Americas to increase their wealth and broaden their influence over world affairs. The Spanish were among the first Europeans to explore the New World and the first to settle in what is now the United States.

By 1650, however, England had established a dominant presence on the Atlantic coast. The first colony was founded at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Many of the people who settled in the New World came to escape religious persecution. The Pilgrims, founders of Plymouth, Massachusetts, arrived in 1620. In both Virginia and Massachusetts, the colonists flourished with some assistance from Native Americans. New World grains such as corn kept the colonists from starving while, in Virginia, tobacco provided a valuable cash crop. By the early 1700s enslaved Africans made up a growing percentage of the colonial population. By 1770, more than 2 million people lived and worked in Great Britain's 13 North American colonies.

DUTCH IN AMERICA: 1624-1664

In 1621 the States General in the Netherlands grant a charter to the Dutch West India Company, giving it a monopoly to trade and found colonies along the entire length of the American coast. The area of the Hudson river, explored by Hudson for the Dutch East India Company in 1609, has already been designated New Netherland. Now, in 1624, a party of thirty families is sent out to establish a colony. They make their first permanent settlement at Albany, calling it Fort Orange.

In 1626 Peter Minuit is appointed governor of the small colony. He purchases the island of Manhattan from Indian chiefs, and builds a fort at its lower end. He names the place New Amsterdam. The Dutch company finds it easier to make money by piracy than by the efforts of colonists (the capture of the Spanish silver fleet off Cuba in 1628 yields vast profits), but the town of New Amsterdam thrives as an exceptionally well placed seaport - even though administered in a harshly authoritarian manner by a succession of Dutch governors.

The only weakness of New Amsterdam is that it is surrounded by English colonies to the north and south of it. This place seems to the English both an anomaly and an extremely desirable possession. Both themes are reflected in the blithe grant by Charles II in 1664 to his brother, the duke of York, of the entire coastline between the Connecticut and Delaware rivers.

New Amsterdam, and in its hinterland New Netherland, lie exactly in the middle of this stretch. When an English fleet arrives in 1664, the Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant accepts the reality of the situation and surrenders the territory without a shot being fired. Thus New Amsterdam becomes British and two years later, at the end of hostilities between Britain and the Netherlands, is renamed New York. The town has at the time about 1500 inhabitants, with a total population of perhaps 7000 Europeans in the whole region of New Netherland - which now becomes the British colony of New York.

The Dutch have recently begun to settle the coastal regions further south, which the British now also appropriate as falling within the region given by Charles II to the duke of York. It becomes the colony of New Jersey.

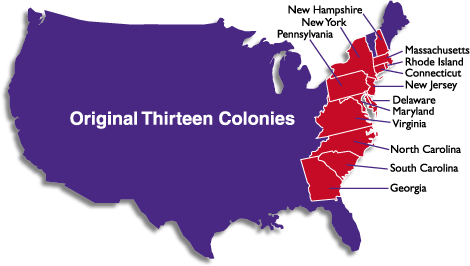

ORIGINAL THIRTEEN COLONIES

Seeking independence from England and the British Crown, thirteen American colonies declared themselves sovereign and independent states. Their official flag is shown to the left. In the early history of America, western borders of most colonies varied some from the modern-day state borders shown to the left - because in the west - the British still controlled vast territories up to the Mississippi River. At that time the colony of Virginia included all of the lands of what is now called West Virginia. In the end the thirteen colonies were: Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts Bay, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Jersey were formed by mergers of previous colonies.

THE WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE OF THE BRITISH COLONIES IN NORTH AMERICA.

The Thirteen Colonies were British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States. The colonies were: Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts Bay, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island and Providence. Each colony developed its own system of self government. The white Americans were mostly independent farmers, who owned their own land and voted for their local and provincial government. Benjamin Franklin in 1772, after examining the wretched hovels in Scotland surrounding the opulent mansions of the land owners, said that in New England every man is a property owner, "has a Vote in public Affairs, lives in a tidy, warm House, has plenty of good Food and Fuel, with whole clothes from Head to Foot, the Manufacture perhaps of his own family.

Before independence, the thirteen were part of a larger set of colonies in British America. Those in the British West Indies, Canada, and East and West Florida remained loyal to the crown throughout the war, although there was a degree of sympathy with the Patriot cause in several of them. However, their geographical isolation and the dominance of British naval power precluded any effective participation.

Government. British settlers did not come to the American colonies with the intention of creating a democratic system, yet by doing without a land-owning aristocracy they created a broad electorate and a pattern of free and frequent elections that put a premium on voter participation. The colonies offered a much broader franchise than England or indeed any other country. Americans enjoyed the thrill of voting and exercised it often. White men with enough property could vote for members of the lower house of the legislature, and in Connecticut and Rhode Island they could even vote for governor.

Legitimacy for a voter meant having an "interest" in society – as the South Carolina legislature said in 1716,, "it is necessary and reasonable, that none but such persons will have an interest in the Province should be capable to elect members of the Commons House of Assembly. Women, children, indentured servants and slaves were subsumed under the interest of the family head. The main legal criterion for having an "interest" was ownership of property, which was narrowly based in Britain, and nineteen out of twenty men were controlled politically by their landlords.

London insisted on it for the colonies, telling governors to exclude man who were not freeholders (that is, did not own land) from the ballot. Nevertheless land was so widely owned that 50% to 80% of the white men were eligible to vote. The colonial political culture emphasized deference, so that local notables were the men who ran and were chosen. But sometimes they competed with each other, and had to appeal to the common man for votes. There were no political parties, and would-be legislators formed ad-hoc coalitions of their families, friends, and neighbors.

Outside Puritan New England, election day brought in all the men from the countryside to the county seat to make merry, politick, shake hands with the grandees, and meet old friends, hear the speeches and all the while toasting, eating, treating, tippling, gaming and gambling. They voted by shouting their choice to the clerk, as supporters cheered or booed. Candidate George Washington spent L39 for treats for his supporters. The candidates knew they had to "swill the planters with bumbo (rum)." Elections were carnivals where all men were equal for one day and traditional restraints relaxed.

The actual rate of voting ranged from 20% to 40% of all adult white males. The rates were higher in Pennsylvania, New York, where long-standing factions, based on ethnic and religious groups, mobilize supporters at a higher rate. New York and Rhode Island developed long-lasting two-faction systems that held together for years at the colony level, but did not reach into local affairs. The factions were based on the personalities of a few leaders and arrays of family connection, and had little basis in policy or ideology. Elsewhere the political scene was in a constant whirl, and based on personality rather than long-lived factions or serious disputes on issues.

The colonies were independent of each other before 1774 as efforts led by Benjamin Franklin to form a colonial union through the Albany Congress of 1765 had not made progress. The thirteen all had well established systems of self government and elections based on the Rights of Englishmen, which they were determined to protect from imperial interference. The "vast majority" of white men were eligible to vote.

Economic policy

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its colonies. Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants--and kept others out--by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximize exports from and minimize imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling--which became a favorite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch [11] The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the British Navy captured New Amsterdam (New York) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.

Coming of American revolution

Beginning with the intense protests over the Stamp Act of 1765, the Americans insisted on the principle of "no taxation without representation". They argued that, as the colonies had no representation in the British Parliament, it was a violation of their rights as Englishmen for taxes to be imposed upon them. Those other British colonies that had assemblies largely agreed with those in the Thirteen Colonies, but they were thoroughly controlled by the British Empire and the Royal Navy, so protests were hopeless

Parliament rejected the colonial protests and asserted its authority by passing new taxes. Trouble escalated over the tea tax, as Americans in each colony boycotted the tea and in Boston, dumped the tea in the harbor during the Boston Tea Party in 1773. Tensions escalated in 1774 as Parliament passed the laws known as the Intolerable Acts, which, among other things, greatly restricted self-government in the colony of Massachusetts. In response the colonies formed extralegal bodies of elected representatives, generally known as Provincial Congresses, and later that year twelve colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the Second Continental Congress the thirteenth colony, Georgia, sent delegates. By spring 1775 all royal officials had been expelled from all thirteen colonies. The Continental Congress served as a national government through the war that raised an army to fight the British and named George Washington its commander, made treaties, declared independence, and instructed the colonies to write constitutions and become states.

Other British colonies

At the time of the war Britain had seven other colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America: Newfoundland, Rupert's Land (the area around the Hudson Bay), Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, East Florida, West Florida, and the Province of Quebec. There were other colonies in the Americas as well, largely in the British West Indies. These colonies remained loyal to the crown.

Newfoundland stayed loyal to Britain without question. It was exempt from the Navigation Acts and shared none of the grievances of the continental colonies. It was tightly bound to Britain and controlled by the Royal Navy and had no assembly that could voice grievances. Nova Scotia had a large Yankee element that had recently arrived from New England, and shared the sentiments of the Americans about demanding the rights of the British men. The royal government in Halifax reluctantly allowed the Yankees of Nova Scotia a kind of "neutrality." In any case, the island-like geography and the presence of the major British naval base at Halifax made the thought of armed resistance impossible.

Quebec was inhabited by French Catholic settlers who came under British control in the previous decade. The Quebec Act of 1774 gave them formal cultural autonomy within the empire, and many priests feared the intense Protestantism in New England. The American grievances over taxation had little relevance, and there was no assembly nor elections of any kind that could have mobilized any grievances. Even so the Americans offered membership in the new nation and sent a military expedition that failed to capture Canada in 1775. Most Canadians remained neutral but some joined the American cause.

In the West Indies the elected assemblies of Jamaica, Grenada, and Barbados formally declared their sympathies for the American cause. The possibilities for overt action were sharply limited by the overwhelming power of Royal Navy in the islands. During the war there was some opportunistic trading with American ships. In Bermuda and the Bahamas local leaders were angry at the food shortages caused by British blockade of American ports. There was increasing sympathy for the American cause, including smuggling, and both colonies were considered "passive allies" of the United States throughout the war. When an American naval squadron arrived in the Bahamas to seize gunpowder, the colony gave no resistance at all.

East Florida and West Florida were new royal territories, transferred to Britain during the French and Indian War. The few British colonists there needed protection from attacks by Indians and Spanish privateers. After 1775, East Florida became a major base for the British war effort in the South, especially in the invasions of Georgia and South Carolina. However, Spain seized Pensacola in West Florida in 1781, and won both colonies in the Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1783. Spain ultimately transferred both Florida colonies to the United States in 1819.

MODERN HISTORY OF AMERICAN COLONIES