Опыт анализа “small/little” на материале Британского национального корпуса

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ МОСКОВСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ

ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ

ВЫСШЕГО ПРОФЕССИОНАЛЬНОГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ

«МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ОБЛАСТНОЙ

СОЦИАЛЬНО-ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ ИНСТИТУТ»

ФАКУЛЬТЕТ иностранных языков

КАФЕДРА английского языка

СПЕЦИАЛЬНОСТЬ 033200.00 «Английский язык

с дополнительной специальностью французский язык»

«Допущена к защите»

Декан

Д.п.н., профессор Саламатина Ирина Ивановна

« ____ » ___________________ 2011 г.

Зав. кафедрой

К.ф.н., доцент Мигдаль Ирина Юрьевна

« ____ » ___________________ 2011 г.

Опыт анализа “small/little” на материале Британского национального корпуса

ВЫПУСКНАЯ КВАЛИФИКАЦИОННАЯ РАБОТА

Выполнил:

студент очной формы обучения

Алякринский Александр Петрович

Руководитель:

К.ф.н., доцент Сазонова Татьяна Александровна

Рецензент:

К.п.н Онищенко Юлия Юрьевна

Коломна – 2011 г.

Investigation of Semantically-Related Words “Small/Little” in the British National Corpus

Supervisor: Sazonova Tatiana Alexandrovna

Student: Alyakrinskiy Alexander Petrovich

Contents

Introduction……………………………………………………………….…….4

Chapter 1: Corpus Linguistics and Language Study.................................5

1.1Corpus Linguistics and Its Methodology…………….…………….……..9

1.2 Different Corpora for Different Purposes……….………………………15

1.3Practical Applications of Language Corpora……………………………19

Chapter 2: Investigation of Semantically-Related Words “Small/Little” in the British National Corpus…………………………...……...…….………..30

2.1 The British National Corpus: Structure and Composition………………30

2.2 The Results of Investigation of Semantically-Related Words Small/Little in the British National Corpus………………..……..……………………….....32

Conclusion………………………………………………………….……….37

Bibliography…………………………………………………………….…...…40

Introduction

As Prof. Gvishiani puts it, “With the creation of large-scale corpus recourses for the English language the ability to explore its’ performance’ data has been substantially enhanced. Lexicographers, grammarians, and language learners have all benefited from the availability of these resources, and there is little doubt remaining that corpora have introduced a new reality to linguists in all fields of research” [Гвишиани 2008:20].

Indeed, the past twenty years have seen unprecedented changes in many areas of our life, including linguistics. Thanks to the new technologies linguists and lexicographers have been given the ability to collect and store huge quantities of language electronically from all kinds of sources. This collection of texts stored in an electronic database is called the corpus. The exploitation of corpus data in linguistic studies has lead to the appearance of a new branch of linguistics-corpus linguistics.

Having heard a declaration that corpora will revolutionize language teaching, I became very inquisitive to find out for myself what corpus studies have to offer the English language teacher and how feasible such an implementation would be.

Perhaps, the use of real examples of texts in the study of language is not a new issue in the history of linguistics. However, Corpus Linguistics has developed considerably in the last decades due to the great possibilities offered by the processing of natural language with computers. The availability of computers and machine-readable texts made it possible to get data quickly and easily and also to have this data presented in a format suitable for analysis.

At the click of a button, the linguist can now assemble corpora ad hoc, selected according to specific language varieties, genres, topics and etc.., and the specific function for the analysis for a given application. Nowadays anybody who owns a PC (and most people do) is able to assemble materials from the Web, scan electronic databases on CD-ROM or connect to one by remote access.

Therefore, computerized corpora are useful to dictionary makers and others in establishing patterns of language that are not apparent from the introspection. Such patterns can be very helpful in highlighting meanings, including parts of speech, and words that co-occur with some frequency. Further, while it may appear that synonymous words can be used in place of one another, corpora can show that it is not in fact common for words to be readily substitutable [Finegan 2004].

Our research paper belongs to corpus-based studies. As for theoretical basis, we proceed from the works written by such prominent scholars as Leech G., Granger S., Scott M., Meyer Ch., McEnery T., Sinclair J., Gvishiani N. and many others.

The main aim of the research is to investigate lexical peculiarities of semantically-related words small/little in the British National Corpus.

The aim of the research is to be reached through solving the following tasks:

- To define the term “corpus”;

- To characterize the term “corpus linguistics”;

- to analyze the meaning of the words “small” and “little” in the British National Corpus;

- to determine words typically used with “small” and “little” in the British National Corpus;

To achieve the aim and fulfill the tasks set before us we have used the following methods:

- the technique of concordance lines;

- the use of the frequency analysis;

- the use of Key Word in Context Option (KWIC);

As for the structure of the research work, it consists of Introduction, two Chapters and five Paragraphs, Conclusion and References. Introduction includes the explanation of the main aim of our research work, concrete tasks, through which the aim is considered to be reached and the methods of the research.

Chapter concerns the role of computer corpora, its main characteristics and the use of it for different purposes. Also the chapter includes general features of the term “Corpus Linguistics” and the history of its development. In Chapter we use Corpus Linguistics for investigating linguistic peculiarities of semantically-related words small/little in the British National Corpus. In Conclusion we summarize the results of our research work. Bibliography contains a list of scientific literature and websites we have used in our research paper.

The approbation of the paper: the main results of the research work have been reported at the annual Students’ Scientific Conferences at Moscow State Regional Social Humanities Institute (March 2011), Academy of Federal Security Service and Moscow State University (April 2011).

Chapter I. What is Corpus and Corpus Linguistics?

We are at the threshold of a new era of English lan�guage studies. Until the last quarter of the 20th century, the scientific study of the language had just two broad traditions. The first was a tradition of historical enquiry, fostered by the comparative studies of the 19th – century philology. The second was a tradition of research into the contemporary language, fostered chiefly by the theories and methods of descriptive linguistics. Now there is a third perspective to consider, stemming from the consequences of the technological revolution, which is likely to have far-reaching effects on the goals and methods of English language research. Due to the great availability of computers and its processing of natural language has made it possible to collect vast amounts of data – corpora were developed.

According to David Crystal “Corpora are large and systematic enterprises: whole texts or whole sections of text are included, such as conversations, magazine articles, newspapers, lectures, broadcasts and chapters of novels” [Crystal 2003].

There is no doubt that developments in electronic instrumentation and computer science have already altered the way we look at the language. The vast data-processing capacity of modern systems has made it possible to expect answers to questions that it would have been impracticable to ask a generation ago. The transferring of the Oxford English Dictionary {OED) onto disk, to take but one example from the 1990s, enables thousands of time-related questions to be asked about the development of the lexicon which it would have been absurd to contemplate before. If you want to find out which words were first attested in English in the year of your birth, according to the OED database, you can now do so, and it takes just a few seconds.

Graeme Kennedy, a famous linguist states that “corpus linguistics is based on bodies of text as the domain of study and as the source of evidence for linguistic description and argumentation. It has also come to embody methodologies for linguistic description in which quantification of the distribution of linguistic items is part of the research activity”[Kennedy 2000].

All areas of English language study have been profoundly affected by technological developments.

In phonetics, new generations of instrumentation are taking forward auditory, acoustic, and articulatory research. In phonology, lexical database are allowing a new range of questions to be asked about the frequency and distribution of English sounds. In graphology, image scanners are enabling large quantities of text to be quickly processed, and image-enhancing techniques are being applied t obscure graphic patterns in old manuscripts. In grammar huge corpora of spoken and written English are making it possible to carry out studies of structures in unprecedented detail and in an unprecedented range of varieties. Discourse analyses are both motivating and benefiting from research in human-computer interaction. And, above all, there has been the remarkable progress made in the study of the lexicon databases giving rise to an explosion of new types of dictionary.

Other well-recognized areas of English language study have also been affected. The new technology supports sociolinguistic studies of dialect variation, providing computer-generated maps and sophisticated statistical processing. Child language acquisition studies have since the 1980s seen the growth of a computer database of transcribed samples from children of different language background (The Child Language Data Exchange System, or CHILDES). In clinical language studies, several aspects of disordered speech are now routinely subjected instrumental and computational analysis. And in stylistics, there is a computational perspective for the study of literary authorship which dates from the 1960s.

As always, faced with technological progress, the role of the human being becomes more critical than ever. From a position where we could see no patterns in a collection of data, an unlimited number of computer-supplied statistical analyses can now make us see all too many. The age has already begun to foster new kinds of English language specialists, knowledgeable in hardware and software, which help process the findings of their computationally illiterate brethren. We can conclude that a well-constructed corpus turns out to be useful in several ways [Meyer 2002].

- CORPUS LINGUISTICS AND ITS METHODOLOGY

Strictly speaking, a corpus is simply a body of text; also it can be described as a large collection of authentic texts that have been gathered in electronic form according to a specific set of criteria. There are four important characteristics to note here: “authentic”, “electronic”, “large”, and “specific criteria”. These characteristics are what make corpora different from other types of text collections and we will examine each of them in turn.

If a text is authentic, that means that it is an example of real “live” language and consists of a genuine communication between people going about their normal business. In other words, the text is naturally occurring and has not been created for the express purpose of being included in a corpus in order to demonstrate a particular point of grammar, etc.

A text in electronic form is one that can be processed by a computer. It could be an essay that you typed into a word processor, an article that you scanned from a magazine, or a text you found on the World Wide Web. By compiling a corpus in electronic form, you not only save trees, you can also use special soft ware packages known as corpus analysis tools to help you manipulate the data. These tools allow you to access and display the information contained within the corpus in a variety of useful ways. Essentially when we consult a printed text, we have to read it from beginning to end, perhaps marking relevant sections with a highlighter or red pen so that to go back and study them more closely at a later date. In contrast, consulting a corpus, we do not have to read the whole text. We can use corpus analysis tools to help you find those specific sections of text that are of interest – such as single words or individual lines of text – and this can be done much more quickly than if you were working with printed text. It is very important to note, however, that these tools do not interpret the data – it is still the responsibility of its users, as linguists, to analyze the information found in the corpus. Corpus Linguistics has generated a number of research methods, attempting to trace a path from data to theory. Wallis and Nelson first introduced what they called the 3A perspective: Annotation, Abstraction and Analysis.

- Annotation consists of the application of a scheme to texts. Annotations may include structural markup, part-of-speech tagging, parsing, and numerous other representations.

- Abstraction consists of the translation (mapping) of terms in the scheme to terms in a theoretically motivated model or dataset. Abstraction typically includes linguist-directed search but may include e.g., rule-learning for parsers.

- Analysis consists of statistically probing, manipulating and generalising from the dataset. Analysis might include statistical evaluations, optimisation of rule-bases or knowledge discovery methods.

The advantage of publishing an annotated corpus is that other users can then perform experiments on the corpus. Linguists with other interests and differing perspectives than the originators can exploit this work. By sharing data, corpus linguists are able to treat the corpus as a locus of linguistic debate, rather than as an exhaustive fount of knowledge. [Wallis, Nelson 2003]

We can name such corpora endlessly and be sure that each of them serves a definite function, without which any linguist can’t live. Electronic texts can also be gathered and consulted more quickly than printed texts, because technology makes it easier for people to compile and consult corpora. Moreover corpus can be used by anyone who wants to study authentic examples of language use. Therefore, it is not surprising that they have been applied in a wide range of disciplines and have been used to investigate a broad range of linguistic issues.

Due to the great possibilities offered by computer technologies Corpus Linguistics has developed. According to the computational linguist and lexicographer John Sinclair: “Corpus Linguistics is- a study of language that includes all processes related to processing, usage, and analysis of written or spoken machine-readable corpora [Meyer 2002].

There are a number of defining features in establishing the fundamentals of corpora-based studies. Let us consider them one by one.

The subject of corpus linguistics is the exploration of real language on computer, a microcosm of its use that represents the language at least to some extent, for purposes of greater accuracy and precision in defining and demonstrating its various aspects. There are at least two basic features identifying this approach:

- Access to lengthy chunks of texts from a variety of genres and registers, and

- Preventing “ overgeneralization” when decisions about language are taken on the of scanty empirical evidence.

Another major advantage of corpus analysis is that it liberates language researchers from the drudgery involved in collecting every bit of material to be analyzed and enables them to focus their creative energies on doing what machine cannot do. More fundamental, however, is “the power of this analysis to uncover totally new facts about the language”.

Corpus linguistics considers not only speech, but language as well, arguably, in a new light, providing a new vision and a more powerful potential, which derives from a mere quantity of language samples, a growing scale of their coverage [Gvishiani 2008].

The object under investigation is the speaker’s (writer’s) output, the product, the result of the speaker’s activity in constructing speech. This is a multifaceted phenomenon which thrives on the speaker’s knowledge of the language as well as his/her “linguistic behavior’ as a member of a given speech community and a “carrier” of a given linguistic culture.

What makes corpus linguistics so exciting is the analysis of “choices” made by the speaker. The question can be formulated as follows: what is normal as against what is possible? Here corpus linguistics links up with cognitive studies because most choices are essentially “knowledge-based” and oriented towards a given linguistic culture, i.e. depend on our perception and understanding of the world. Speaking about language as such we can assume that some choices are governed by the structure of language, some are individual, but there are choices which present a tendency characterizing language items quantitatively, i.e. in terms of their frequency and utility. With automated linguistic analysis one has an excellent opportunity to gauge the way in which some items become a preferred choice of speakers, are getting more frequent and prominent. This is how idiomatic usage can be divided from samples of non-idiomatic speech revealing the particular areas of overuse, “underuse”, and error which speakers of English as a foreign language are prone to [Gvishiani 2008]

As a method corpus linguistics relates to synchronic contrastive studies aimed at establishing facts of differences and similarities among languages,dialects,or varieties of language in the course of their scientific description. When the method is seen as the focus of attention, the advantages of using corpora become obvious. Functional- synchronic analyses of languages are best developed on a solid foundation of broad empirical evidence. For example, such varieties of ‘World Englishes’ as learner English and native-speaker English had remained largely neglected until new technologies were introduced into contrastive studies of stretches of speech [Crystal 2003].

Most lexical corpora today are POS-tagged. However even corpus linguists who work with 'unannotated plain text' inevitably apply some method to isolate terms that they are interested in from surrounding words. In such situations annotation and abstraction are combined in a lexical search [Johanson 1991].

The advantage of publishing an annotated corpus is that other users can then perform experiments on the corpus. Linguists with other interests and differing perspectives than the originators can exploit this work. By sharing data, corpus linguists are able to treat the corpus as a locus of linguistic debate, rather than as an exhaustive fount of knowledge.

The obvious achievements in the exploitation of corpus data have led to further questions concerning the place of corpus linguistics in the hierarchy of language studies, its claims and applications as a branch of linguistics. But is it a branch of linguistics? The answer to this question is both yes and no. Corpus linguistics is not a branch of linguistics in the same sense as syntax, semantics, sociolinguistics and so on. . All of these disciplines concentrate on describing/explaining some aspect of language use. Corpus linguistics in contrast is a methodology rather than an aspect of language requiring explanation or description. Corpus linguistics is a methodology that may be used in almost any area of linguistics, but it does not truly delimit an area of linguistics itself.

Corpus linguistics does, however, allow us to differentiate between approaches taken to the study of language and, in that respect, it does define an area of linguistics or, at least, a series of areas of linguistics. Hence we have corpus-based syntax as opposed to non-corpus-based syntax, corpus-based semantics as opposed to non-corpus-based semantics and so on. So, while corpus linguistics is not an area of linguistic enquiry itself, it does, at least, allow us to discriminate between methodological approaches taken to the same area of enquiry by different groups, individuals or studies [McEnery 2005].

Considering its name, corpus linguistics derives its novelty and originality from the use of corpora-large quantities of natural, real language, taken from a variety of sources and lumped together in a computerized system, so that people, dictionary people in particular, can study the meanings and patterns that emerge. This suggests that corpus building activities present a new strategy not only as a Method highlighting the evidence of “real language” but also as a theoretical approach providing new insights into the nature of previously formulated notions. The term “corpus linguistics” refers not just to a new computer-based methodology, but, as Leech puts it, to a “new research enterprise”, a new way of thinking about language, which is challenging some of the deeply-rooted ideas” [Leech 1992].

Corpus linguistics has undergone a remarkable renaissance in recent years. From being a marginalized approach used largely in English linguistics, and more specifically in studies of English grammar, corpus linguistic has started its scope. The history of corpus linguistics exists almost as a body of academic folklore. The use of collections of text in language study is not a new idea. In the Middle Ages work began on making lists of all the words in a particular texts, together with their contexts - what we today call concordancing. Other scholars counted word frequencies from single texts or from collections of texts and produced lists of the most frequent words. Areas where corpora were used include language acquisition, syntax, semantics, and comparative linguistics, among others. Even if the term 'corpus linguistics' was not used, much of the work was similar to the kind of corpus based research linguists do today with one great exception - they did not use computers [Gvishiani 2008].

McEnery and Wilson use the term “early corpus linguistics” for all linguistic corpus-based work done before the advent of Chomsky. That covers the period of time up to the end of the 1950s when structuralism was the basic linguistic science. Famous linguists of the structuralist tradition like Boas, Sapir, Bloomfield and Harris use methods for their analysis of language that can be undoubtedly called corpus-based. However, the term `corpus linguistics is not yet explicitly used during that time but comes up later.

- DIFFERENT CORPORA FOR DIFFERENT PURPOSES

There are almost as many different types of corpora as there are types of investigations. Language is so diverse and dynamic that it would be hard to imagine a single corpus that could be used as a representative sample of all language. At the very least, we would need to have different corpora for different natural languages, such as English, French, Spanish, etc., but even we run into problems because the variety of English is not the same as that spoken in America, New Zealand, Jamaica, etc. And within each of these language varieties, we will find that people speak to their friends differently from the way they speak to their friends’ parents, and that people in the 1800s spoke differently from the way they do nowadays, etc. Having said this, it is still possible to identify some broad categories of corpora that can be compiled on the basis of different criteria in order to most different aims. The following list of different types of corpora is not exhaustive, but it does provide an idea of some of the different types of corpora that can be compiled [Crystal 2003].

General reference corpus vs. special purpose corpus: A general reference corpus is one that can be taken as representative of a given language as a whole and can therefore be used to make general observations about that particular language. This type of corpus typically contains written and spoken material, a broad cross-section of text types (a mixture of newspapers, fiction, reports, radio and television broadcasts, debates, etc.) and focuses on language for general purposes(i.e. the language used by ordinary people in everyday situations. In contrast, a special purpose corpus is one that focuses on a particular aspect of a language. It could be restricted to the LSP of a particular subject field, to a specific text type, to a particular language variety or to the language used by members of a certain demographic group (e.g. teenagers). Because of its specialized nature, such a corpus cannot be used to make observations about language in general. However, general reference corpora and special purpose corpora can be used in a comparative fashion to identify those features of a specialized language that differ from general language.

Written vs. spoken corpus: A written corpus is a corpus that contains texts that have been written, while a spoken corpus is one that consists of transcripts of spoken material (e.g. conversations, broadcasts, lectures, etc.) Some corpora, such as the British National Corpus, contain a mixture of both written and spoken texts.

Monolingual vs. multilingual corpus: A monolingual corpus is one that contains texts in a single language, while multilingual corpora contain texts in two or more languages. Multilingual corpora can be further subdivided into parallel and comparable corpora. Parallel corpora contain texts in language alongside their translations into language. Comparable corpora do not contain translated texts. The texts in comparable corpus were originally written in different language, but they all have the same communicative function. In other words, they are all on the same subject, all the same type of text (e.g. instruction manual, technical report, etc.), all from the same time frame.

Synchronic vs. diachronic corpus: A synchronic corpus presents a snap-shot of language use during limited time frame, whereas a diachronic corpus can be used to study how a language has evolved over a long period of time.

Open vs. closed corpus: An open corpus, also known as a monitor corpus, is one that is constantly being expanded. This type of corpus is commonly used in lexicography because dictionary makers need to be able to find out about new words or charges in meaning. In contrast, a closed or finite corpus is one that does not get augmented once it has been compiled. Given the dynamic nature of LSP and the importance of staying abreast of current developments in the subject field, open corpora are likely to be of more interest for LSP users.

Learner corpus: A learner corpus is one that contains texts written by learners of a foreign language. Such corpora can be usefully compared with corpora of texts written by native speakers. In this way, teachers, students or researchers can identify the types of errors made by language learners [Meyer 2002].

Now I’d like to advert the concrete examples of corpora. Thanks to the efforts of many now well-known computational linguists, such as: Catherine Ball (Georgetown University) ; Michael Barlow (Rice University) ; James Tang Boyland (Carnegie Mellon University) ; Tim Johns (University of Birmingham) ; Geoffrey Leech (Lancaster University) well-known Computer Corpora have been created. Most of the major world languages have their own corpora. A well-recognized example is the British National Corpus, which is used as a model for many modern corpora. The British National Corpus (BNC) contains more than 360 million words in nearly 150,000 text corpus of samples of written and spoken English from a wide range of sources, designed to represent a wide cross-section of British English from the later part of the 20th century, both spoken and written.

The written part of the BNC (90%) includes, for example, extracts from regional and national newspapers, specialist periodicals and journals for all ages and interests, academic books and popular fiction, published and unpublished letters and memoranda, school and university essays, among many other kinds of text. The spoken part (10%) consists of orthographic transcriptions of unscripted informal conversations (recorded by volunteers selected from different age, region and social classes in a demographically balanced way) and spoken language collected in different contexts, ranging from formal business or government meetings to radio shows and phone-ins [Gvishiani 2008].

It’s important to note that work on building the corpus began in 1991, and was completed in 1994. No new texts have been added after the completion of the project.

Another example is the American National Corpus. The American National Corpus (ANC) project is creating a massive electronic collection of American English, including texts of all genres and transcripts of spoken data produced from 1990 onward. It consists of 100 million of words. The ANC will provide the most comprehensive picture of American English ever created, and will serve as a resource for education, linguistic and lexicographic research, and technology development.

Also we can’t but mention the Canadian Corpus (CONTE). The corpus is conceived as spanning the period from the earliest Ontarian English texts to the end of the 19th century (ca. 225,000 words). In its pre-Confederation section (pC), i.e. 1776 - 1850, CONTE-pC comprises about 125,000 words in three genres. The Corpus of Early Ontario English, as the first electronic corpus of a variety of earlier Canadian English aims to add a diachronic dimension to the study of Ontario English and thus to complement the historical picture of Canadian English in general. [Renouf 2003]

We can not ignore the Russian National Corpus. It consists of 200 million of words and covers primarily the period from the middle of the 18th to the early 21st centuries. This period represents the Russian language of both the past and the present in a wide range of sociolinguistic variants: literary, colloquial, vernacular, in part dialectal. The Corpus includes original (non-translated) works of fiction (prose, drama and poetry) of cultural importance which are interesting from a linguistic point of view. Apart from fiction, the Corpus includes a large volume of other sources of written (and, for the later period, spoken) language: memoirs, essays, journalistic works, scientific and popular scientific literature, public speeches, letters, diaries, documents, etc. [Crystal 2003].

Also there are such corpora as The International Corpus of Learner English. The Louvain Centre for English Corpus Linguistics has played a pioneering role in promoting computer learner corpora (CLC) and was among the first, if not the first, to begin compiling such a corpus and it is the result of over ten years of collaborative activity between a number of universities internationally and currently contains over 3 million words of writing by learners of English from 21 different mother tongue backgrounds. The writing in the corpus has been contributed by advanced learners of English as a foreign language rather than as a second language and is made up of 21 distinct sub-corpora, each containing one language variety.

1.3 PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS OF LANGUAGE CORPORA

Most of the major world languages have their own corpora. From the point of view of the corpus user I’ll just mention some corpora, distinguishing them according to the function they can have and the insights they can offer for different types of linguistic enquiry.

In the field of multilingual resources, translation scholars and contrastive linguists prioritise different types of corpora depending on whether they are focusing on translation as a process or as a product. When working across language it is advisable to consider the evidence of both translational corpora and comparable corpora because they have different things to offer.

Translational corpora are corpora of texts which stand in a translational relationship of each other, that is to say the texts can each be a translation of an absent original and the others translations. A translation corpus can be used to shed light on the process of translation itself. The most common use of a translation corpus, however, remains the access to translations as products where the translated corpora reveal cross-linguistic correspondences and differences that are impossible to discover in a monolingual corpus. Within translation corpora we should differentiate between parallel corpora and free translation corpora.

The original parallel corpora were truly parallel. The software for aligning them relied entirely on a close, sentence-by-sentence correspondence between the two texts. Before parallel corpora, pretty well all translations were free translations. Translation was a fairly mysterious human skill, and judgement was by results; the method was not normally open for investigation. The application of computers to the communication industry has put pressure on people to modify their behaviour to accommodate the machines, and as a result the strict literal translations have become a growth industry, and all sorts of tools have become available which allow a translator to see much of a text as a repetition of an earlier text with small variations.

Because of misgiving about the representativeness of strictly parallel corpora, and the poor range of choice of material translated in such a rigorous fashion, it has been customary to build up comparable corpora. Comparable corpora are corpora whose components are chosen to be similar samples of their respective languages in terms of external criteria such as spoken vs. written language, register,etc [Johanson 1991].

In the field of language varieties an important milestone is the assembly of the International Corpus of English (ICE) with the primary aim of providing material for comparative studies of varieties of English throughout the world. Twenty centers around the world are now making available corpora of their own national or regional variety of English, ranging from Canada to the Caribbean, Australia, Kenya, South Africa, India, Singapore, Honk Kong,etc. Each ICE corpus consists of spoken and written material put together according to a common corpus design. So the ICE corpora can also be considered comparable in terms of size. They all contain 500 texts each of approximately 2,000 words for a total of one million words, date of texts (1990 to 1996), authors and speakers (aged eighteen and over, educated through the medium of English, both males and females) and text categories (spoken, written, etc.). Each of the component corpora can stand alone as a valuable resource for the investigation of national or regional variety. Their value is enhanced by their compatibility with each other.

In the field of LSP, many corpora of restricted varieties are being assembled for teaching purposes very much in line with a shift towards vocational language training where students of economics, for example, are exposed preferentially to the type of language they will be using, i.e. the language of economic texts, journals or spoken negotiations. Nowadays it is quite easy to gain access to a CD-ROM of a specific newspaper or magazine.

Another type of corpus which is specifically focusing on the teaching process and is particularly useful for error analysis is what is referred to as a learner corpus. This can be used to identify characteristic patterns in student’s writing. It is a useful diagnostic tool for both learners and teachers and can be used to detect characteristics errors made by an individual student engaged in a specific activity. It offers the possibility of identifying the text type and subject discipline where errors occur most frequently, enabling the teacher to pre-teach and so pre-empt common errors. It encourages and enhances a shift towards learner autonomy, and, when proper guidance is given, it enables the language learner to become researcher and to develop the skills required to identify, explain and rectify recurrent errors. A learner corpus can become a source of learning materials and activities. With the possibility of access to large corpora, newspaper collections, etc. students can compare across corpora and discover similarities and differences in native speaker and non-native speaker usage.

In this respect it is important to remember that corpus work should always be comparative and evidence from a specific-domain corpus should be compared with evidence from a general purpose corpus, whether the focus is on LSP, translation, the learning process itself or something else. This is particularly important in the context of language teaching where the corpus can offer students an approximation to first-hand language experience. Of course, this also poses the problem of assembling general purpose corpora which can be taken as representative of the language as a whole.

The problem of corpus representativeness is central to corpus linguistics and issues such as defining a target population and sampling become very important when assembling a corpus. Most of these general corpora a very large indeed (300 million words) and are becoming even larger, so they are beyond the undertaking of a single individual.

The question arises “what role do corpora play in language studies”? First and for most the role of corpora in lexicography can’t be overestimated. Nowadays dictionaries can be produced and revised much more quickly than before.

Lexicographers made use of empirical data long before the discipline of corpus linguistics was invented. Samuel Johnson, for example, illustrated his dictionary with examples from literature, and in the nineteenth century the Oxford English Dictionary made use of citation slips to study and illustrate word usage. The practice of citation collecting still continues, but corpora have changed the way in which lexicographers — and other linguists interested in the lexicon — can look at language.

Corpora, and other (non-representative) collections of machine readable text, now mean that the lexicographer can sit at a computer terminal and call up all the examples of the usage of a word or phrase from many millions of words of text in a few seconds. This means not only that dictionaries can be produced and revised much more quickly than before — thus providing more up-to-date information about the language — but also that the definitions can (hopefully) be more complete and precise, since a larger sample of natural examples is being examined. To illustrate the benefits of corpus data in lexi�cography we may cite briefly one of the findings from Atkins and Levin's (1995) study of verbs in the semantic class of'shake'. In their paper, they quote the definitions of these verbs from three dictionaries — the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (1987,2nd ed.), the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (1989,4th ed.) and the Collins COBUILD Dictionary (1987,1st ed.). Let us look at an aspect of just two of the entries they discuss - those for quake and quiver. Both the Longman and COBUILD dictionaries list these verbs as being solely intransitive, that is they never take a direct object; the Oxford dictionary simi�larly lists quake as intransitive only, but lists quiver as being also transitive, that is, it can sometimes take an object. However, looking at the occurrences of these verbs in a corpus of some 50,000,000 words, Atkins and Levin were able to discover examples of both quiver and quake in transitive constructions (for example, It quaked her bowels; quivering its wings). In other words, the dictionar�ies had got it wrong: both these verbs can be transitive as well as intransitive. This small example thus shows clearly how a sufficiently large and representa�tive corpus can supplement or refute the lexicographer's intuitions and provide information which will in future result in more accurate dictionary entries.

The examples extracted from corpora may also be organized easily into more meaningful groups for analysis, for instance, by sorting the right-hand context of a word alphabetically so that it is possible to see all instances of a particular collocate together. Furthermore, the corpora being used by lexi�cographers increasingly contain a rich amount of textual information - the Longman-Lancaster corpus, for example, contains details of regional variety, author gender, date and genre - and also linguistic annotations, typically part-of-speech tagging. The ability to retrieve and sort information according to these variables means that it is easier (in the case of part-of-speech tagging) to specify which classes of a homograph the lexicographer wants to examine and (in the case of textual information) to tie down usages as being typical of particular regional varieties, genres and so on.

It is in dictionary building that the concept of an open-ended monitor corpus has its greatest role, since it enables the lexicographer to keep on top of new words entering the language or existing words changing their meanings or the balance of their use accord�ing to genre, formality and so on. But the finite sampled type of corpus also has an important role in lexical studies and this is in the area of quantification. Although frequency counts, such as those of Thorndike and Lorge (1944), predate modern corpus linguistic methodologies, they were based on smaller, less representative corpora than are available today and it is now possible to produce frequencies more rapidly and more reliably than before and also to subdivide these across various dimensions, according to the varieties of a language in which a word is used. More frequency information is already begin�ning to appear in published dictionaries. The third edition of the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (1995), for example, indicates whether a word occurs amongst the 1,000,2,000 or 3,000 most frequent words in spoken and written English respectively. There is now an increasing interest in the frequency analysis of word senses and it should only be a matter of time before corpora are being used to provide word sense frequencies in dictionaries.

The ability to call up word combinations rather than individual words and the existence of tools, such as mutual information for establishing relationships between co-occurring words, mean that it is also now feasi�ble to treat phrases and collocations more systematically than was previously possible. For instance, again in the third edition of the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, bar charts are now provided showing the collocational preferences of certain key words. The verb try, for example, has a chart show�ing the frequencies of different grammatical patterns: try to do something, try something, try and do something, try doing something and so on. Word co�occurrences are important for a number of reasons. For instance, a phraseological unit may constitute a piece of technical terminology or an idiom, and collocations are important clues to specific word senses. Techniques for identifying such combinations in text corpora mean that, like individual words, they can now be better treated in dictionaries and in machine-readable terminology banks for professional tech�nical translators.

As well as word meaning, we may also consider under the heading of lexi�cal studies corpus-based work on morphology (word structure).The fact that morphology deals with language structure at the level of the word may suggest that corpora do not have any great advantage here over other sources of data such as existing dictionaries or introspection. However, corpus data do have an important role to play in studying the frequencies of different morphological variants and the productivity of different morphemes. Opdahl (1991), for example, has used the LOB and Brown corpora to study the use of adverbs which may or may not have a -ly suffix (e.g. low/lowly), finding that the forms with the -ly suffix are more common than the 'simple' forms and that, contrary to previous claims, the 'simple' forms are somewhat less common in American than in British English.

Now, we can see how a corpus, being naturalistic data, can help to define more clearly which forms are most frequently used and begin to suggest reasons why this may be so[McEnery, Wilson 2005].

We have already seen how a corpus may be used to look at the occurrences of individual words in order to determine their meanings (lexical semantics), primarily in the context of lexicography. But corpora are also important more generally in semantics. Here, their main contribution has been that they have been influential in establishing an approach to semantics which is objective and which takes due account of indeterminacy and gradience.

The first important role of the corpus, as demonstrated by Mindt, is that it can be used to provide objective criteria for assigning meanings to linguistic items [Mindt 1991]. Mindt points out that most frequently in semantics the meanings of lexi�cal items and linguistic constructions are described by reference to the linguist's own intuitions, that is, by what we have identified as a rationalist approach. However, he goes on to argue that in fact semantic distinctions are associated in texts with characteristic observable contexts - syntactic, morpho�logical and prosodic — and thus that, by considering the environments of the linguistic entities, an empirical objective indicator for a particular semantic distinction can be arrived at. Mindt presents three short studies in semantics to back up this claim. By way of illustration, let us take just one of these — that of 'specification' and futurity. Mindt is interested here in whether what we know about the inherent futurity of verb constructions denoting future time can be shown to be supported by empirical evidence; in particular, how far does the sense of futurity appear to be dependent on co-occurring adverbial items which provide separate indications of time (what he terms'specification') and how far does it appear to be independently present in the verb construction itself? Mindt looked at four temporal constructions — namely, will, be going to, the present progressive and the simple present — in two corpora — the Corpus of English Conversation and a corpus of twelve contemporary plays — and examined the frequency of specification with the four different constructions. He found in both corpora that the simple present had the highest frequency of specification, followed in order by the present progressive, will and be going to. The frequency analysis thus established a hierarchy with the two present tense constructions at one end of the scale, often modified adverbially to intensify the sense of future time, and the two inherently future-oriented constructions at the other end, with a much lesser incidence of additional co-occurring words indicating futurity. Here, therefore, Mindt was able to demonstrate that the empirical analysis of linguistic contexts is able to provide objective indica�tors for intuitive semantic distinctions: in this example, inherent futurity was shown to be inversely correlated with the frequency of specification [Mindt 1991].

The second major role of corpora in semantics has been in establishing more firmly the notions of fuzzy categories and gradience. In theoretical linguis�tics, categories have typically been envisaged as hard and fast ones, that is, an item either belongs in a category or it does not. However, psychological work on categorisation has suggested that cognitive categories typically are not hard and fast ones but instead have fuzzy boundaries so that it is not so much a question of whether or not a given item belongs in a particular category as of how often it falls into that category as opposed to another one. This has impor�tant implications for our understanding of how language operates: for instance, it suggests that probabilistically motivated choices of ways of putting things play a far greater role than a model of language based upon hard and fast cate�gories would suggest. In looking empirically at natural language in corpora it becomes clear that this 'fuzzy' model accounts better for the data: there are often no clear-cut category boundaries but rather gradients of membership which are connected with frequency of inclusion rather than simple inclusion or exclusion. Corpora are invaluable in determining the existence and scale of such gradients [McEnery 2005].

Resources and practices in the teaching of languages and linguistics typically reflect the division in linguistics more generally between empirical and rational�ist approaches. Many textbooks contain only invented examples and their descriptions are based apparently upon intuition or second-hand accounts; other books - such as the books produced by the Collins cobuild project -are explicitly empirical and rely for their examples and descriptions upon corpora or other sources of real life language data.

The increasing availability of multilingual parallel corpora makes possible a further pedagogic application of corpora, namely as the basis for translation teaching. Whilst the assessment of translation is frequently a matter of style rather than of right and wrong, and therefore perhaps does not lend itself to purely computer-based tutoring, a multilingual corpus has the advantage of being able to provide side-by-side examples of style and idiom in more than one language and of being able to generate exercises in which students can compare their own translations with an existing professional translation or original. Such an approach is already being pioneered at the University of Bologna using corpora which, although they do not contain the same text in more than one language, do contain texts of a similar genre which can be searched for relevant examples.

Parallel corpora are also beginning to be harnessed for a form of language teaching which focuses especially on the problems that speakers of a given language face when learning another. For example, at Chemnitz University of Technology work is under way on an internet grammar of English aimed particularly at German-speaking learners. An example of the sort of issue that this focused grammar will highlight is aspect, an important feature of English grammar but one which is completely missing from the grammar of German. The topic will be introduced on the basis of relatively universal principles (reference time, speech time and event time) and the students will be helped to see how various combinations of these are encoded differently in the two languages. The grammar will make use of a German-English parallel corpus to present the material within an explicitly contrastive framework. The students will also be able to explore grammatical phenomena for themselves in the corpus as well as working with interactive online exercises based upon it.

It is not a secret that it is now a commonplace in linguistics that texts contain the traces of the social conditions of their production. But it is only relatively recently that the role of a corpus in telling us about culture has really begun to be explored. After the completion of the LOB corpus of British English, one of the earliest pieces of work to be carried out was a comparison of its vocabulary with that of the earlier parallel American Brown corpus (Holland and Johansson 1982). This revealed interesting differences which went beyond the purely linguistic ones such as spelling (e.g. colour/color) or morphology (e.g. got/gotten). Roger Fallon, in association with Geoffrey Leech, has picked up on the potential of corpora in the study of culture. Leech and Fallon (1992) used as their initial data the results of the earlier British and American frequency comparisons, along with the kwic concordances to the two corpora to check up on the senses in which words were being used. They then grouped those differences which were found to be statistically significant into fifteen broad domain cate�gories. The frequencies of concepts within these categories in the British and American corpora revealed findings which were suggestive not primarily of linguistic differences between the two countries but of cultural differences. For example, words in the domains of crime and the military were also more common in the American data and, in the crime category, 'violent' crime was more strongly represented in American English than in British English, perhaps suggestive of the American 'gun culture'. In general, the findings from the two corpora seemed to suggest a picture of American culture at the time of the two corpora (1961) that was more macho and dynamic than British culture. Although such work is still in its infancy and requires methodological refinement, it seems an interesting and promising line which, pedagogically, could also more closely integrate work in language learning with that in national cultural studies [McEnery 2005].

Chapter II. Investigation of Semantically-Related Words “Small/Little” in the British National Corpus

2.1 The British National Corpus: Structure and Composition

In this chapter we’ll describe and illustrate the possible use of the British National Corpus for investigation. I’d like to consider the British national Corpus in detail. I have mentioned that the British National Corpus (BNC) is a 100-million-word text corpus of samples of written and spoken

English from a wide range of sources. It was compiled as a general corpus (collection of texts) in the field of

corpus linguistics. The corpus covers

British English of the late twentieth century from a wide variety of genres with the intention that it be a representative sample of spoken and written British English of that time.

The written part of the BNC (90%) includes, for example, extracts from regional and national newspapers, specialist periodicals and journals for all ages and interests, academic books and popular fiction, published and unpublished letters and memoranda, school and university essays, among many other kinds of text. The spoken part (10%) consists of orthographic transcriptions of unscripted informal conversations (recorded by volunteers selected from different age, region and social classes in a demographically balanced way) and spoken language collected in different contexts, ranging from formal business or government meetings to radio shows and phone-ins [Gvishiani 2008: 65]. There are several sorts of the British National Corpus :

Monolingual: It deals with modern British English, not other languages used in Britain. However non-British English and foreign language words do occur in the corpus.

Synchronic: It covers British English of the late twentieth century, rather than the historical development which produced it.

General: It includes many different styles and varieties, and is not limited to any particular subject field, genre or register. In particular, it contains examples of both spoken and written language.

Sample: For written sources, samples of 45,000 words are taken from various parts of single-author texts. Shorter texts up to a maximum of 45,000 words, or multi-author texts such as magazines and newspapers, are included in full. Sampling allows for a wider coverage of texts within the 100 million limit, and avoids over-representing idiosyncratic texts.

The British National Corpus lets you gain better insight into e-texts and analyse language objectively and in depth. Its lets you count words, make word lists, word frequency lists, and indexes. It has widespread applications in content analysis, language engineering, linguistics, data mining, lexicography, translation, and numerous commercial areas and academic disciplines. It can make full concordances of publishable quality showing every word in its context, handling texts of almost any size. It can make fast concordances, picking your selection of words from text to facilitate targeted analysis. You can view a full word list, a concordance, and your original text simultaneously, and browse through the original text and click on any word to see every occurrence of that word in its context. A user-definable reference system can let you identify which section of a text each word comes from or which logical category of your choice it belongs to.

You can select and sort words in many ways, search for phrases, do proximity searches, sample words, and do regular expression searches.

The British national Corpus was produced by a consortium of British publishers led by Oxford University Press, and the Bank of English came as the result of a long-term effort of the Collins Cobuild Group. We utilized the software the KWIC ("Key Word in Context") Concordance for building concordance figures. the KWIC Concordance is a corpus analytical tool for making word frequency lists, concordances and collocation tables by using electronic files [http://www.chs.nihon-u.ac.jp/eng_dpt/tukamoto/kwic_e.html].

2.2 The Results of Investigation of Linguistic Peculiarities of Semantically-related Words “small/little” in the British National Corpus

The domain of linguistics that has arguably been studied most from a corpus-linguistic perspective is lexical, or even lexicographical, semantics. Already the early work of pioneers such as Sinclair has paved the way for the study of lexical items, their distribution, and what their distribution reveals about their semantics and discourse functions. A particularly fruitful area has been the study of semantically-related words as probably every corpus linguist has come across the general approach of studying synonyms on the basis of their distributional characteristics. Obviously, synonymy is the most frequently corpus-linguistically studied lexical relation.

It is generally accepted that English is one of the most useful languages used by people around the world as a lingua franca. With English as an international language, people from different countries who speak different native languages are able to communicate with one another [Kirkpatrick 2007]. The language enables them to understand their interlocutor’s speech. Meanwhile, they can also impart information to others through English. As a language with a long history and considerable benefits, it is not surprising to learn the fact that there exist millions of words in English. According to several studies, English tends to have larger number of words, if not the largest, than many other languages [Crystal 2003]. Some of the words have been borrowed from other languages [Finegan 2004].

Quite a few English learners could notice that there are a number of words, known as synonyms, which share similar senses of meaning or semantic features, e.g. big and large. The concept of synonyms plays an important role in English. Learners who wish to improve their English skills really need to be aware of and master synonyms. However, it is often found that, in fact, not all synonyms can be used interchangeably in every context. One has to be used in a particular context, whereas another is appropriate for some other situations. Some synonyms differ in terms of connotations they express, and some are different in regions in which they are used [Trudgill 2003].

Therefore, computerized corpora are useful to dictionary makers and others in establishing patterns of language that are not apparent from the introspection. Such patterns can be very helpful in highlighting meanings, including parts of speech, and words that co-occur with some frequency. Further, while it may appear that synonymous words can be used in place of one another, corpora can show that it is not in fact common for words to be readily substitutable [Finegan 2004].

To appreciate what revisions are made by speakers with regard to semantically-related words “small/little” we may turn to the BNC data.

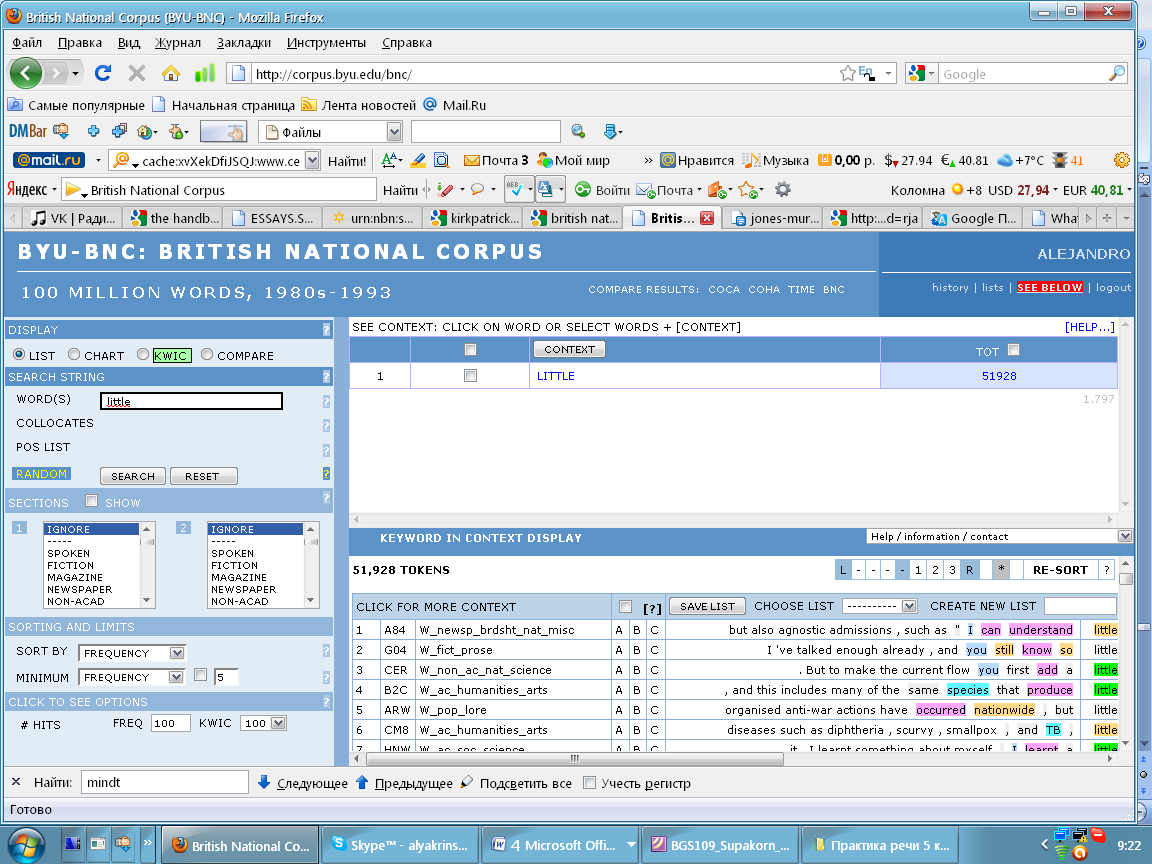

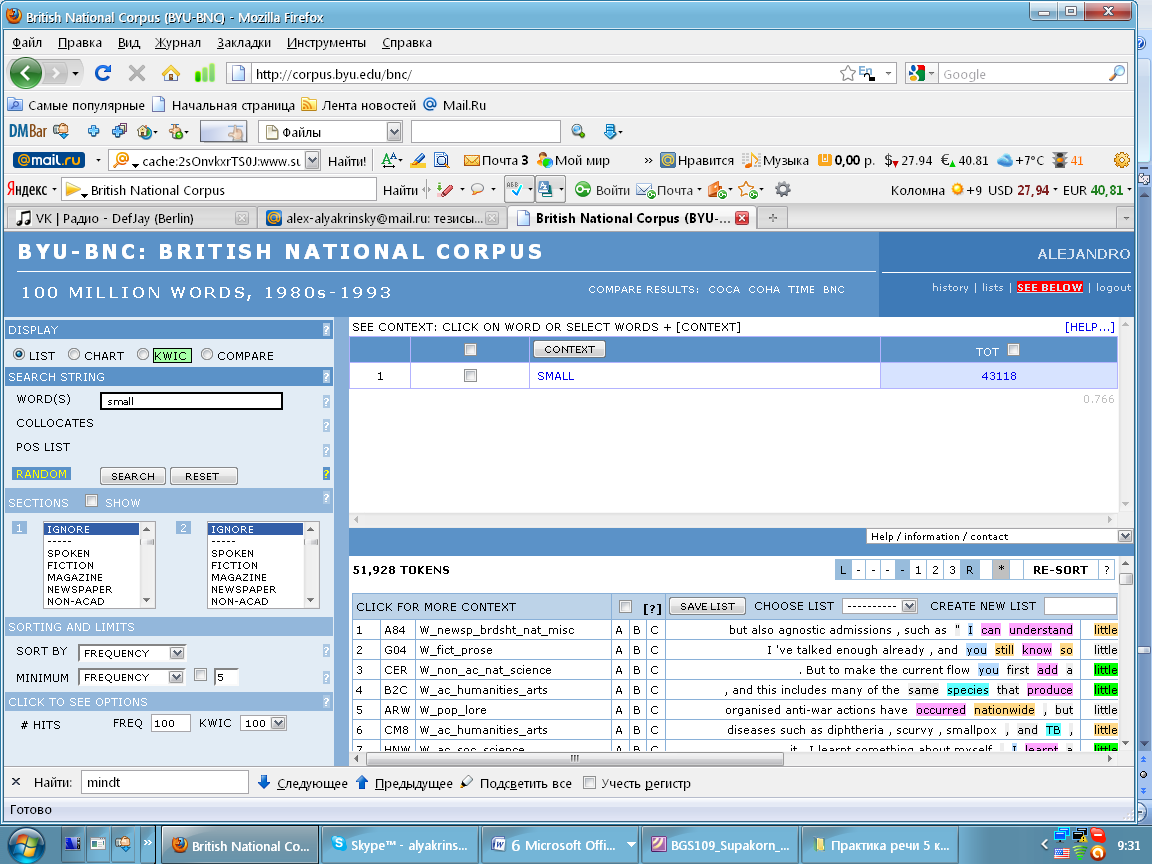

Using the text browser (Screenshots 1 and 2) it can be seen, that according to the British National Corpus there are more cases of using the word ‘little’ (51928) than the word ‘small’ (43118), i.e. the difference is not big, it amounts only to 0,09 %.

Screenshot 1

Screenshot 2

Analyzing definitions from the Macmillan English Dictionary we see that ‘little’ can be used as a determiner, a pronoun, an adverb and adjective. For instance, as a determiner it is often used in the meaning ‘small amount or degree’; ‘not much’: little choice; little progress; ‘hardly any of something’: there’s little point in discussing it any further; there’s little or no hope. Besides ‘little’ is often used with the article ‘a’, meaning ‘some, but not a lot’: a little time left. In spoken English it’s more usual to say ‘a bit of’, ‘a little bit’: We knew a little bit more; a bit of money. As an adverb little/a little can be used in the meaning ‘slightly’: She trembled a little; a little irritated [http://www.macmillandictionary.com].

Applying KWIC (Key Word in Context) option we singled out a number of instances for analysis that can be interpreted in the following way.

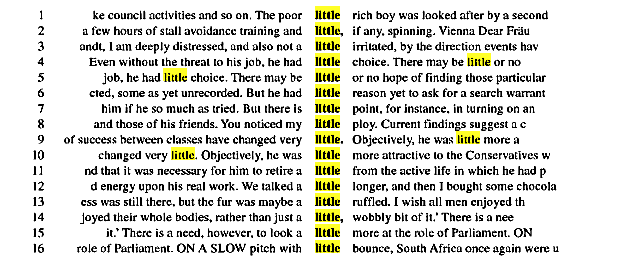

First, Figure 1 shows a selection of entries for the word “little”, and Figure 2 shows a selection of entries for “small”. In Figure 1 quite a few of the sentences wouldn’t tolerate the substitution of small for little- for example 2,3,5,6,9,10,11,15,16,17 and 21. Taking 3 as an example, English does not permit “not a small irritated”. Of those instances where the substitution is possible, several would sound very odd or convey a different connotation, such as 1, 4 and 8.

Figure 1

Little is usually more absolute in its application than ‘small’, and it is preferred to ‘small’ when there is the intent to convey a hint of narrowness, pettiness, unimportance: silly little jokes; little mind.

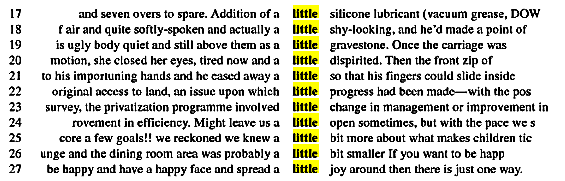

2. From the analysis of a random sample of instances we can observe that the adjective ‘small’, more frequently than the adjective ‘little’, applies to things whose magnitude is determined by number, size, value or significance: a small group; a small house; a small income. ‘Small’ is also used with the words ‘quantity’, ‘amount’, ‘size’, ‘quite’, ‘very’, e.g.: a small quantity of sugar; a very small car (not a very little car).

A characteristic feature of ‘little’, as we think, lies in the fact that it can express either positive or negative connotations, depending on the context. ‘Little’ is appropriate when the context carries connotations of sympathy, tenderness, affection as in the following examples: a little old lady, poor little thing; a pretty little house. And it is used in a negative way for referring to somebody or something you dislike: You little scoundrel! a boring little man.

As the examples in Figure 2 show, little is more readily substitutable for small; part of the reason is that in its use as an adjective little does in fact carry denotations and connotations much like those of most uses of small. However, we observe from Figure 2 that the opposite is not true. This is because little is not only an adjective meaning ‘small’ but also part of an adverb, in the expressions ‘a little ruffled, a little dispirited, and a little open where it modifies an adjective.

Figure 2

Conclusion

In this research work I have tried to explore the notion of corpus linguistics and its application. In the first Chapter I described the role of corpora in the world, its main characteristics and the use of it for different purposes. In the second Chapter I investigated linguistic peculiarities of semantically-related words small/little using the BYU-BNC. During the investigation I faced difficulties working with computer software as many of the programs are unavailable freely on the Internet, others require good understanding of corpus linguistic terms and analysis.

It is evident that corpus linguistics is fast becoming an important subset of applied linguistics as a result of the rise of computers. Computer tools can accurately count the occurrence of linguistic items in texts with tremendous speed and accuracy. They permit the researcher to work with collections of data, too large to do manually and readily search for patterns in order to arrive at generalizations about language use that go beyond mere intuitions. Therefore, corpus-based analysis not only constitutes an extremely useful technological tool, but can be looked at as a type of approaches that makes it possible to do new types of investigations and conduct research on scope previously unfeasible. Without the computer-based corpora and computer programs it is impossible to do this lexical investigation objectively, accurately and efficiently, and to answer the research questions successfully.

Undoubtedly it is an undeniable fact that corpora have a number of features which make them important as sources of data for empirical linguistic research. We have seen a number of these exem�plified in several areas of language study in which corpora have been, and may be, used. In brief the main important advantages of corpora are:

1. Ease of access. Using a corpus means that it is not necessary to go through a process of data collection: all the issues of sampling, collection and encoding have been dealt with by someone else. The majority of corpora are readily available: once the corpus has been obtained, it is also easy to access the data within it, because the corpus is in machine readable form, a concordance program can quickly extract frequency lists and indices of various words or other items within it.

2. Enriched data. Many corpora are now available already enriched with additional interpretive linguistic information such as part-of-speech annotation, grammatical parsing and prosodic transcription. Hence data retrieval from the corpus can be easier and more specific than with annotated data.

3. Naturalistic data. All corpus data are largely naturalistic, unmonitored and the product of real social contexts. Thus the corpus provides the most reliable source of data on language as it is actually used.

4. Because corpus linguistics is a methodology, all linguists could in prin�ciple use corpora in their studies of language: creating dictionaries, studying language change and variation, understanding the process of language acquisition, and improving foreign- and second-language instruction.

5. From the research work we can state that the results we have got are interesting, as the adjectives ‘small’ and ‘little’ carry different denotations and connotations despite being defined as synonyms by many dictionaries. As can be seen, the corpus-based approach to semantically-related words small/little proved to be helpful in language learning and provided the findings that would have been difficult to obtain otherwise.

Coming up to the conclusion I regard corpus-analytic techniques as multi-purpose strategies with an immense potential to enhance all sorts of textual analysis and to confirm or contradict our intuitions about patterns and meanings in literary and non-literary language. However, it is important to be familiar with modern computer software in order to investigate corpus data successfully. I see corpus analysis as a key skill that ought to reach all parts of the discipline as it can be equally applied to linguistics, literary studies, and language teaching. Once John Sinclair said: “Language cannot be invented; it can only be captured” And it can be captured by a corpus.